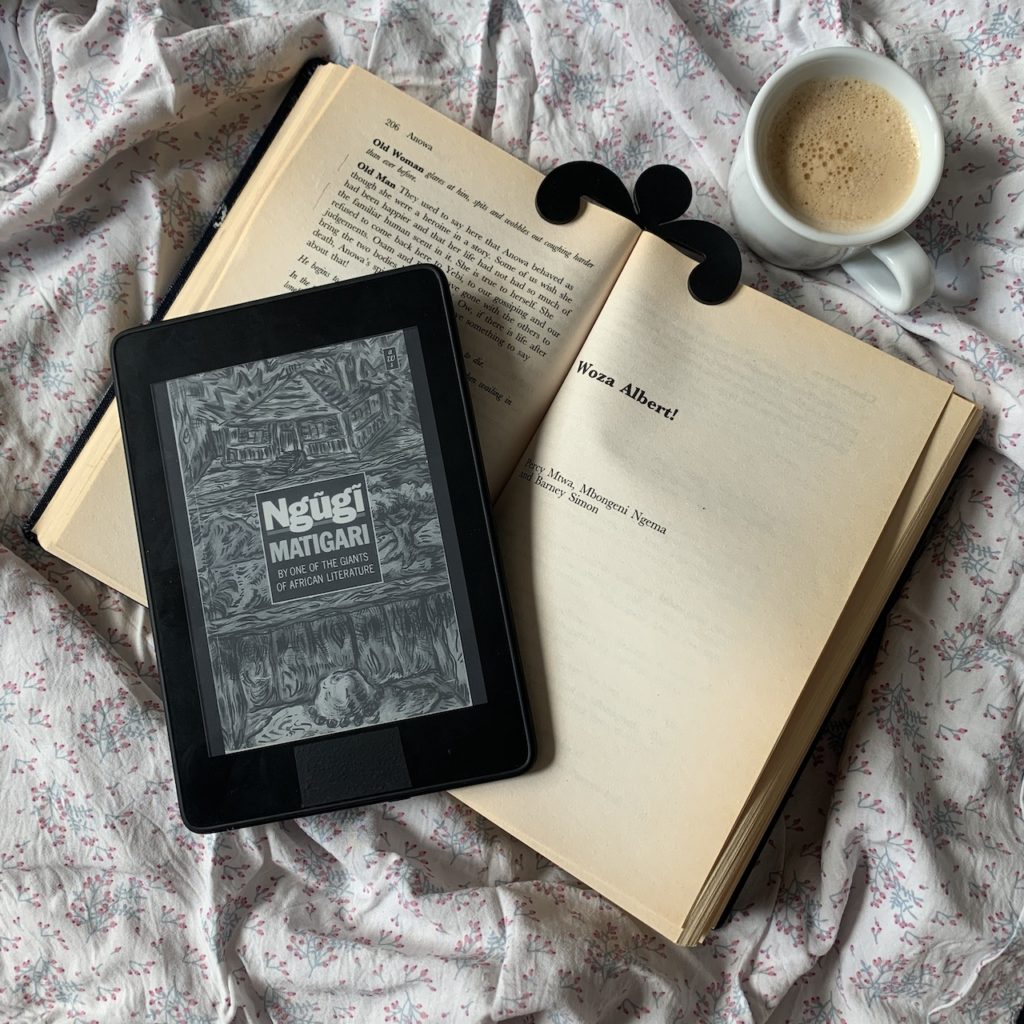

Matigari tells the story of an ageless freedom fighter of the same name, who returns home after spending years in the forest tracking and eventually killing his oppressors, Settler Williams and Mr. Boy. He returns to civilization hoping to be reunited with his family and live free from colonization and exploitation. He quickly finds, however, that the country has traded a foreign oppressor for a local one and begins wandering the country searching for truth and justice. Cobbling together elements of Gikuyu folklore with a distinctly satirical style, Thiong’o’s novel is technically set in a fictional country. Yet, much of the content is reminiscent of postcolonial politics in Kenya at the time of its publication. The protagonist, Matigari, takes on a Christ-like role in the novel with several illusions to the second coming. Similarly,Woza Albert! is a satirical play published and set in apartheid South Africa that envisions Christ’s second coming to South Africa. The play imagines what Christ, called Morena, would think of the segregated state and how the apartheid government would treat him in return.

In both narratives, Matigari and Morena wander the country, interacting with locals and observing daily life through a series of vignettes. Thiong’o employs a critical lens in his portrayal of the public. Each scene opens to a few locals gossiping about Matigari and the fantastical things they’ve heard about him. When he approaches them, he asks the same question each time:

“My friends! Tell me where in this country one can find truth and justice.”

Having not recognized Matigari, they tell him off for asking such ridiculous questions. The novel, therefore, is not only critical of the regime, but also civil society, and its tendency towards idleness. Rather than taking collective action, citizens fantasize about a savior who will save them, while the freedom fighting is left to the revolutionary few.

Conversely, Woza Albert! portrays, with a cautiously upbeat attitude, Black South Africans’ reactions to the news that Morena has arrived in their country. Unlike Thiong’o, Mbongeni Ngema and Percy Mtwa aren’t critical of their cohort and instead, depict their tenacity both to persevere and remain sanguine even under one of the most oppressive regimes in history. Although they don’t hide citizens’ struggles under apartheid, the satirical overlay keeps the piece as playful as it possibly can be. Actors Mbongeni Ngema and Percy Mtwa play all of the roles—a street meat-vender, barber, brickmaker, soldier and more. BBC One Everyman produced a wonderful documentary about Woza Albert! and Ngema and Mtwa’s creative process, which pops up on the internet every now and again. In it, they discuss how they watched specific people in each of the above roles to channel and switch quickly between each fictional character. While the citizens’ parts are highly crafted, Mtwa and Ngema hardly assume the role of Morena. Rather than stoking a specific revolutionary goal, Morena acts as a soundboard for Black South Africans to explain to the audience life in apartheid South Africa and highlight the absurdity of this oppressive, supposedly Christian regime.

Further, both pieces use Christian motifs to highlight the political injustices against Black Kenyans and South Africans. As Christianity was primarily the religion of the colonizer, Thiong’o, Ngema and Mtwa turn these lessons on their head to criticize the oppressor. In both works, readers observe a Christ-like figure who reenacts the cleansing of the Temple of Jerusalem. Similar to the Temple’s “den of thieves,” both regimes use religion to exploit laypeople and profit in the name of the church.

In Woza Albert!, the apartheid government give Morena a tour of the wealthiest parts of the country, including Sun City. When Morena is meant to make a speech supporting the Calvinist country’s economic wealth, he unequivocally condemns it:

“I pass people who sit in dust and beg for work that will buy them bread. And on the other side I see people who are living in gold and glass and whose rubbish bins are loaded with food for a thousand mouths…What country is this?”

Similarly, Matigari commandeers a meeting, which the country’s Minister for Truth and Justice holds in part to settle disgruntled factory workers. He announces that the company owner is giving the heads of state shares in the company stock, so the workers technically now own part of the company. Matigari refutes the Minister’s claim, arguing he’s a puppet of the oppressor and is only making the rich wealthier and the poor workers ever more impoverished:

“What a world! A world in which the tailor wears rags, the tiller eats wild berries, the builder begs for shelter.”

To reinforce the Minister’s loyalty to the ex-colonial regime and their practices, the heads of state all adopt the fictional philosophy of Parratology.

Ultimately, both Morena and Matigari fulfill their missions as Christ-like characters by empowering their Black cohort against their oppressors. After rising from the dead, Morena is finally given a voice in the last scene as he awakes in a graveyard. He and Zuluboy sing:

Yamemeza inkosi yethu

Yathi ma thambo hlanganani

Oyawa vusa amaqhawe amnyama

Wathi kuwo

[Our Lord is calling.

He’s calling for the bones of the dead to join together.

He’s raising up the black heroes.

He calls to them…]

They yell “woza,” meaning ‘come,’ and raise from the dead those the regime murdered for their anti-apartheid activism—Steve Biko, Robert Sobukwe, Albert Luthuli and many more.

Likewise, Matigari revitalizes his community’s revolutionary spirit by taking up arms against the parratologists. Rather than fulfilling the city gossip and acting as their liberator, he places his holy potential back into the citizens’ hands:

“The God who is prophesied is in you, in me and in the other humans. He has always been there inside us since the beginning of time. Imperialism has tried to kilt that God within us. But one day that God will return from the dead. Yes, one day that God within us will come alive and liberate us who believe in Him. I am not dreaming.”

“The flag now belongs to the blacks. So from now onwards, let justice and truth break all the bows drawn in war; let truth and justice settle all the disputes amongst us black people. Let truth and justice rule the world.”

STATS

Title: Matigari

Author: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Translator: Wangûi wa Goro

Publication Year: 1986

Pages: 206

Title: Woza Albert!

Playwrights: Mbongeni Ngema, Percy Mtwa, Barney Simon

Publication Year: 1981

Pages: 80 pages